The Brooklyn Museum is an encyclopedic art museum with a strong commitment to education and the Brooklyn community. The museum's expansive collection and variety of programming have made it a uniquely valuable institution to New York City. Our team was engaged by the Brooklyn Museum's Department of Digital Engagement to analyze how content was being published by the museum and to suggest ways they could make improvements.

Challenge: Develop a comprehensive overview of the museum’s current content, how it’s being produced, and how it’s performing with the museum’s target user populations. Use this information to suggest ways the museum could fill content gaps and improve how its content is being produced.

My Role: Content strategist. I worked with a team of five other content strategists to analyze the museum’s content and suggest ways it could be improved upon.

Project’s Impact: The museum was provided with a detailed analysis of its content and an examination of how well it was serving the museum’s target user populations. A follow-up study, administered after the museum had implemented our recommendations, would be needed to determine their efficacy, but unfortunately that was beyond the scope of the project.

We began by conducting (1)RESEARCH in order to understand the types of content the museum was producing, how it was being produced, and by whom. This research was subsequently analyzed during the (2)SYNTHESIZE stage of our study, at which time we sought to determine if the museum’s content was supporting its target user populations and its short- and long-term goals. Next, we worked to (3)IDEATE solutions that would allow the museum to fill its content gaps and improve its content-production efficiency. Finally, we attempted to (4)VALIDATE our recommendations by presenting our findings to museum leadership and soliciting their feedback.

Our primary contact within the museum was Sara Devine (then Manager of Audience Engagement and Interpretive Materials), whom we met with at the onset of the project. During our initial meeting with Ms. Devine we discussed the museum's current content challenges and their goals for our project. We learned that the museum's staff and budget for content production and maintenance was limited. We also learned that the museum was undergoing a leadership transition; the museum's new leadership had signaled that its current mission and goals (i.e., to serve its local community) would need to be expanded in order to improve the museum’s global visibility and strengthen its reputation as a world-class institution. With these challenges and goals in mind we began our analysis of the museum's content.

Sara Devine of the Brooklyn Museum

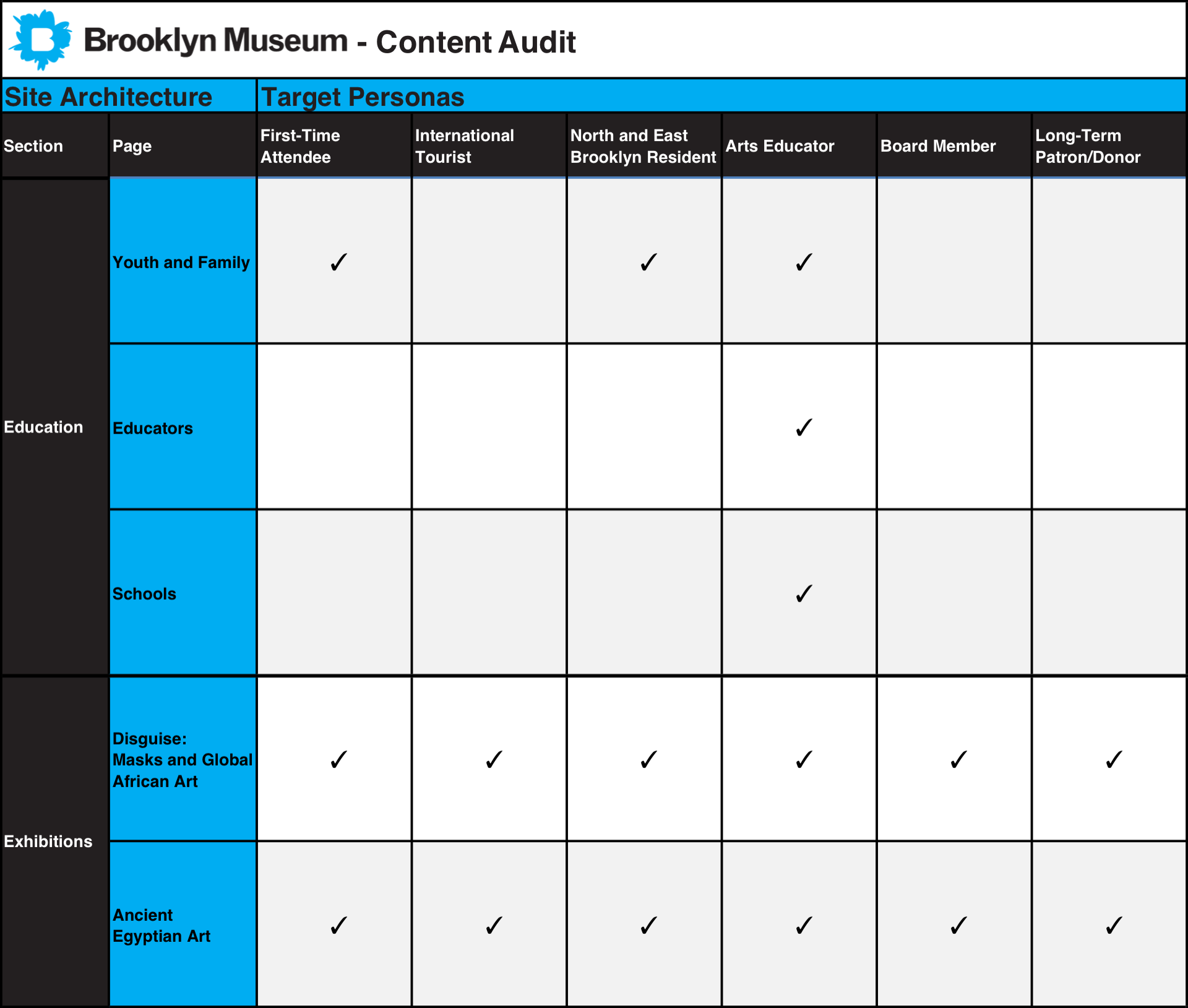

In order to better understand the current state of the museum's digital content, our team performed an audit of their website and social media channels. Each team member was responsible for two sections of the website and two social media channels. Before each of us began work on our respective sections/channels, however, we agreed upon six target personas (Arts Educator, Board Member, First-Time Attendee, International Tourist, Long-Term Patron/Donor, and North & East Brooklyn Resident) who were representative of the populations the museum would need to cater to in order to achieve its current and expanded goals. As we performed our audit we would simultaneously assess how well (or how poorly) the museum's digital content was serving these six target personas (and by extension, the museum's goals).

WEBSITE CONTENT AUDIT

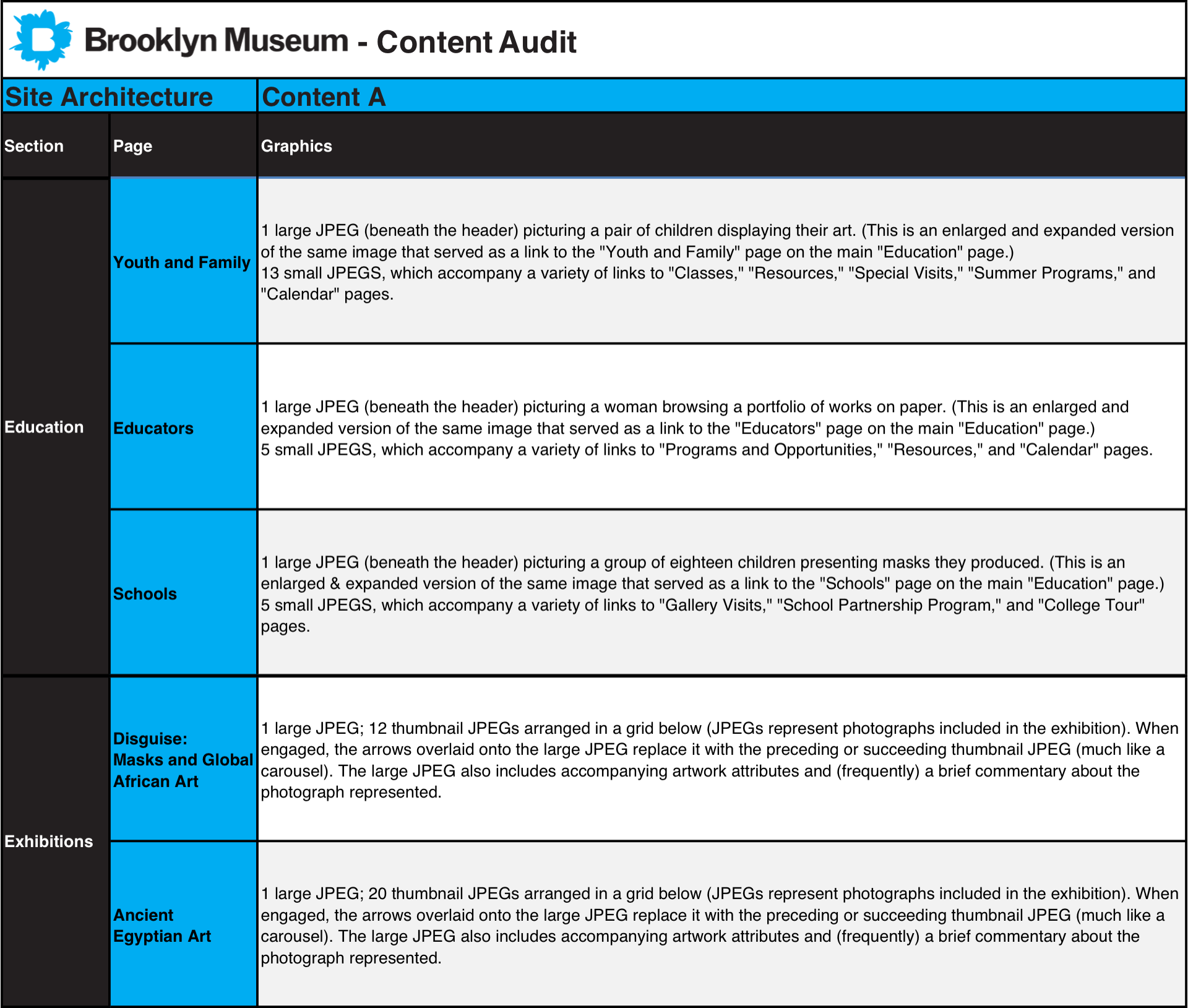

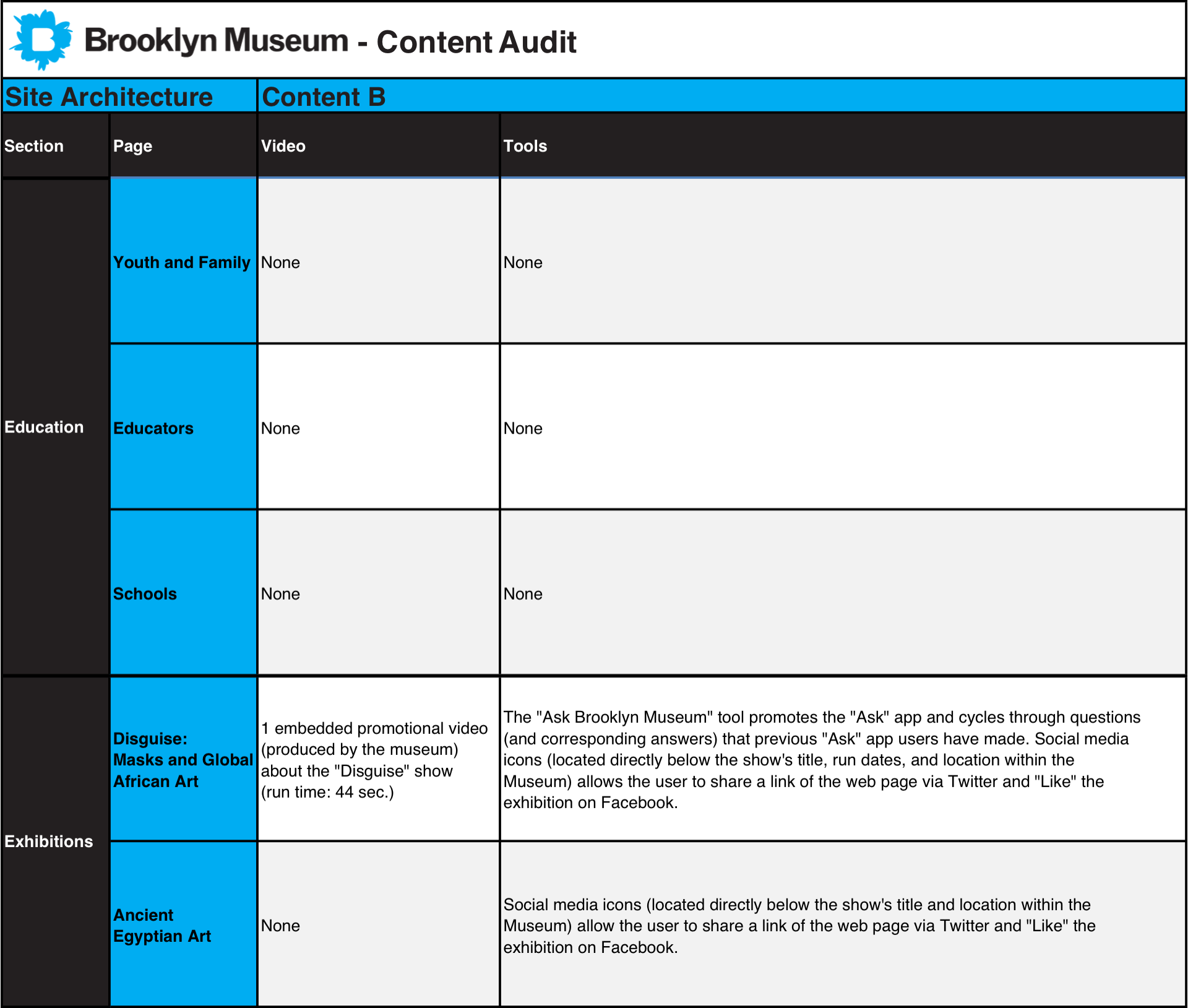

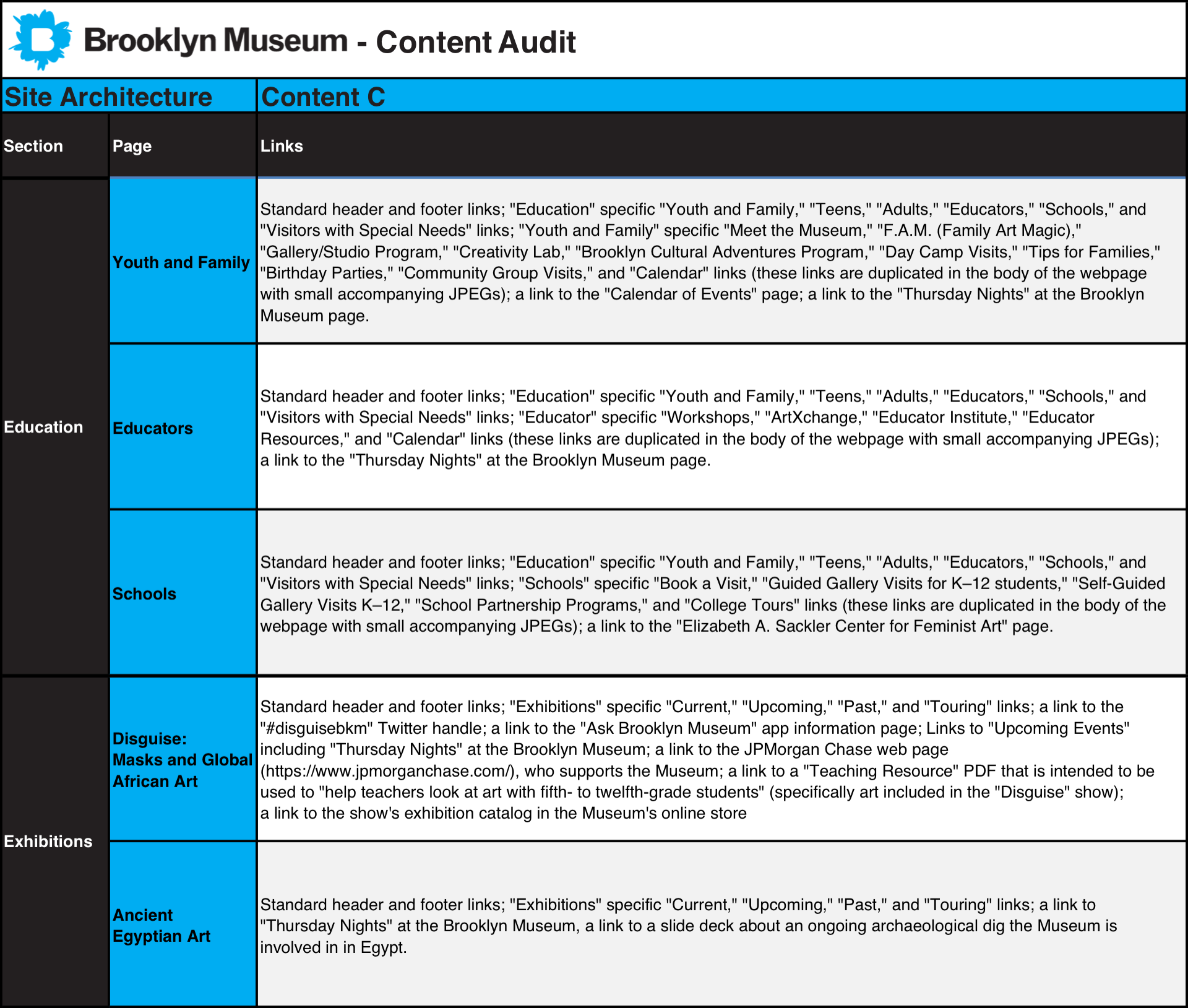

For this portion of the audit my focus was on the content being published to the Education and Exhibitions sections of the museum's website. (A representative sampling of this content has been included in the figure below.) Each member of our team analyzed their respective sections using the same content categories (i.e., graphics, videos, tools, etc.); this would later enable us to uncover inconsistencies in how the museum was publishing their content across the entire website. Each of us also noted which target personas, if any, the content was serving. It quickly became apparent that sections of the website (e.g., Exhibitions) were not presenting content types (e.g., graphics, links, etc.) consistently across individual pages.

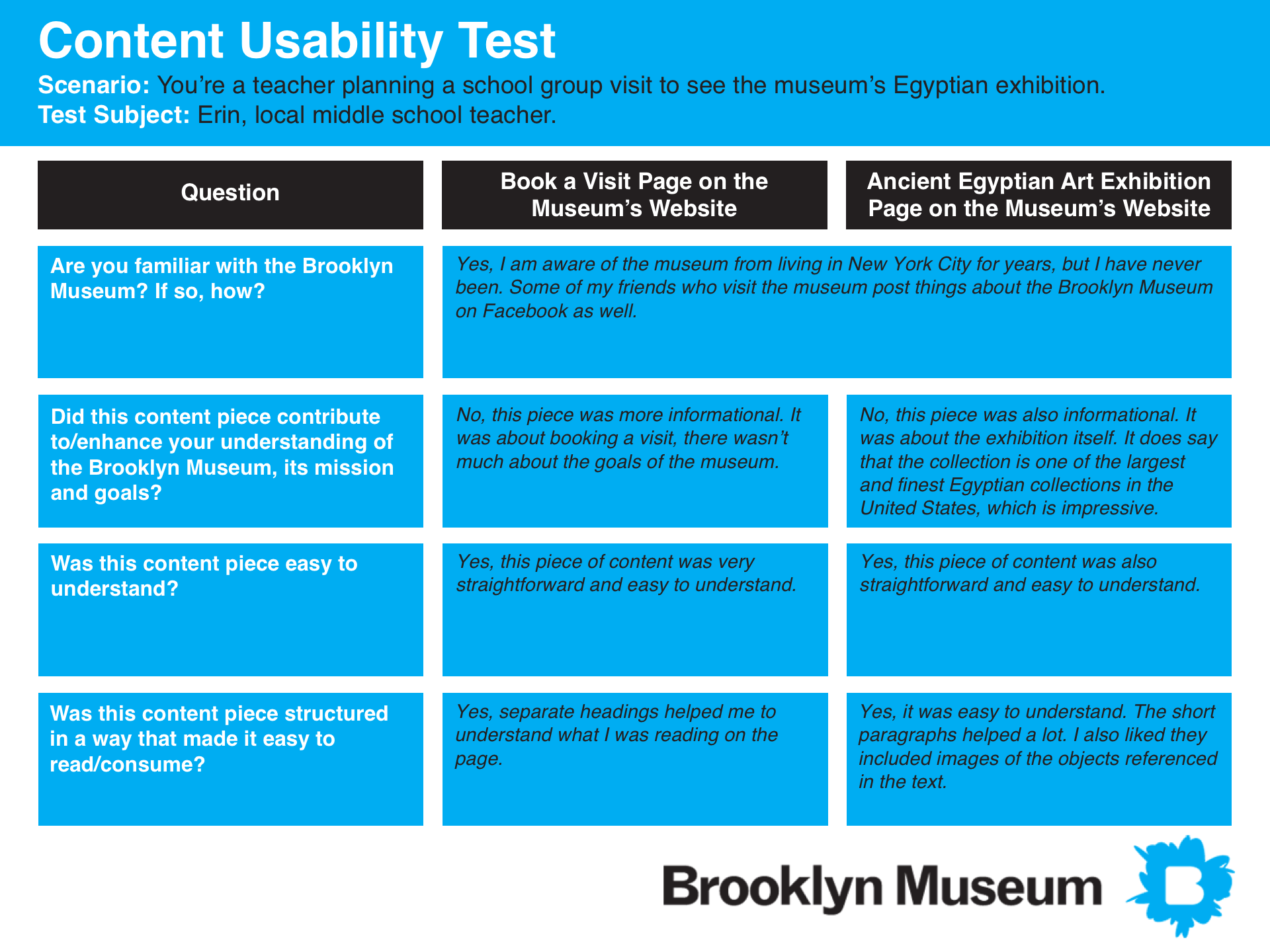

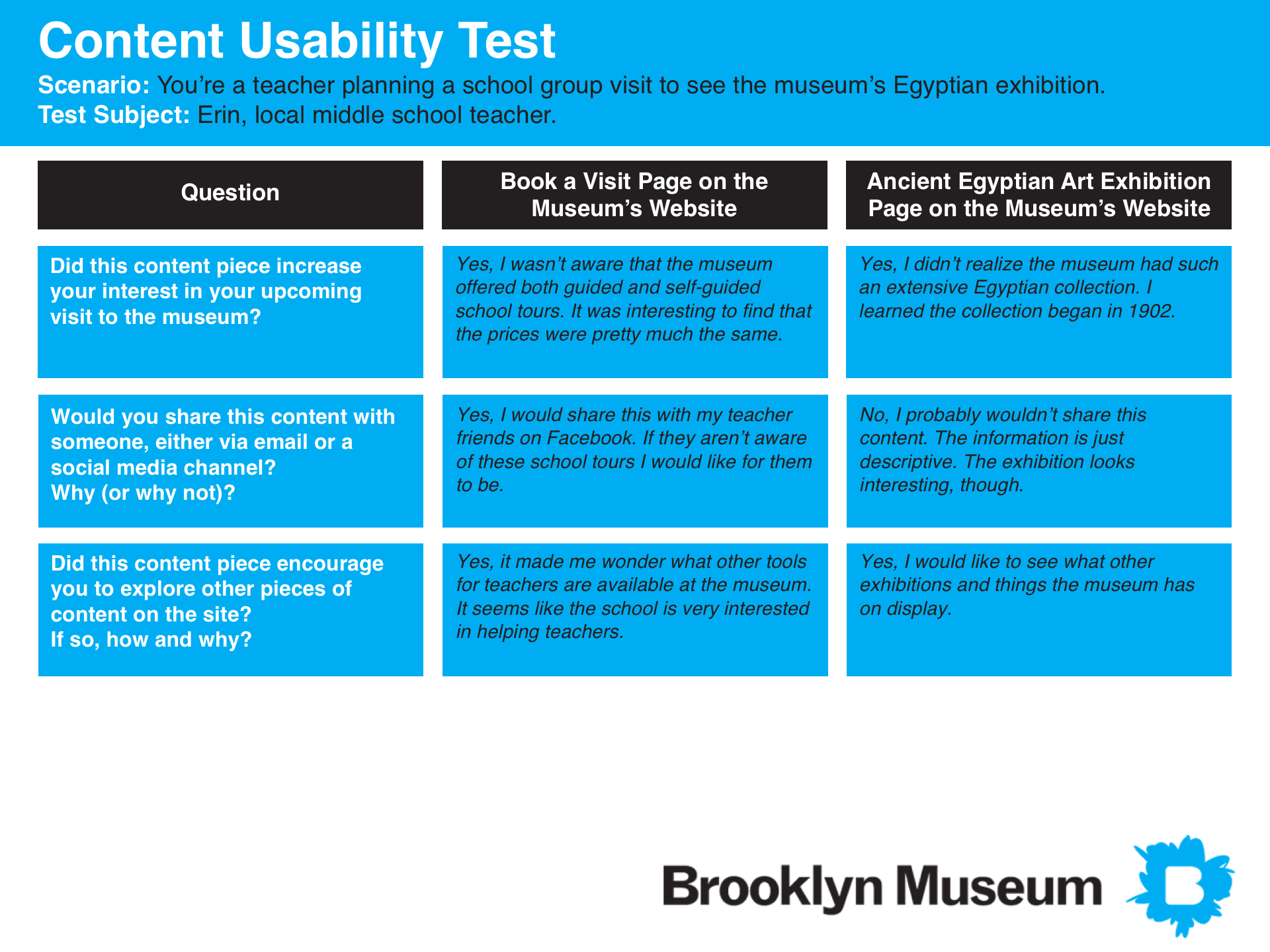

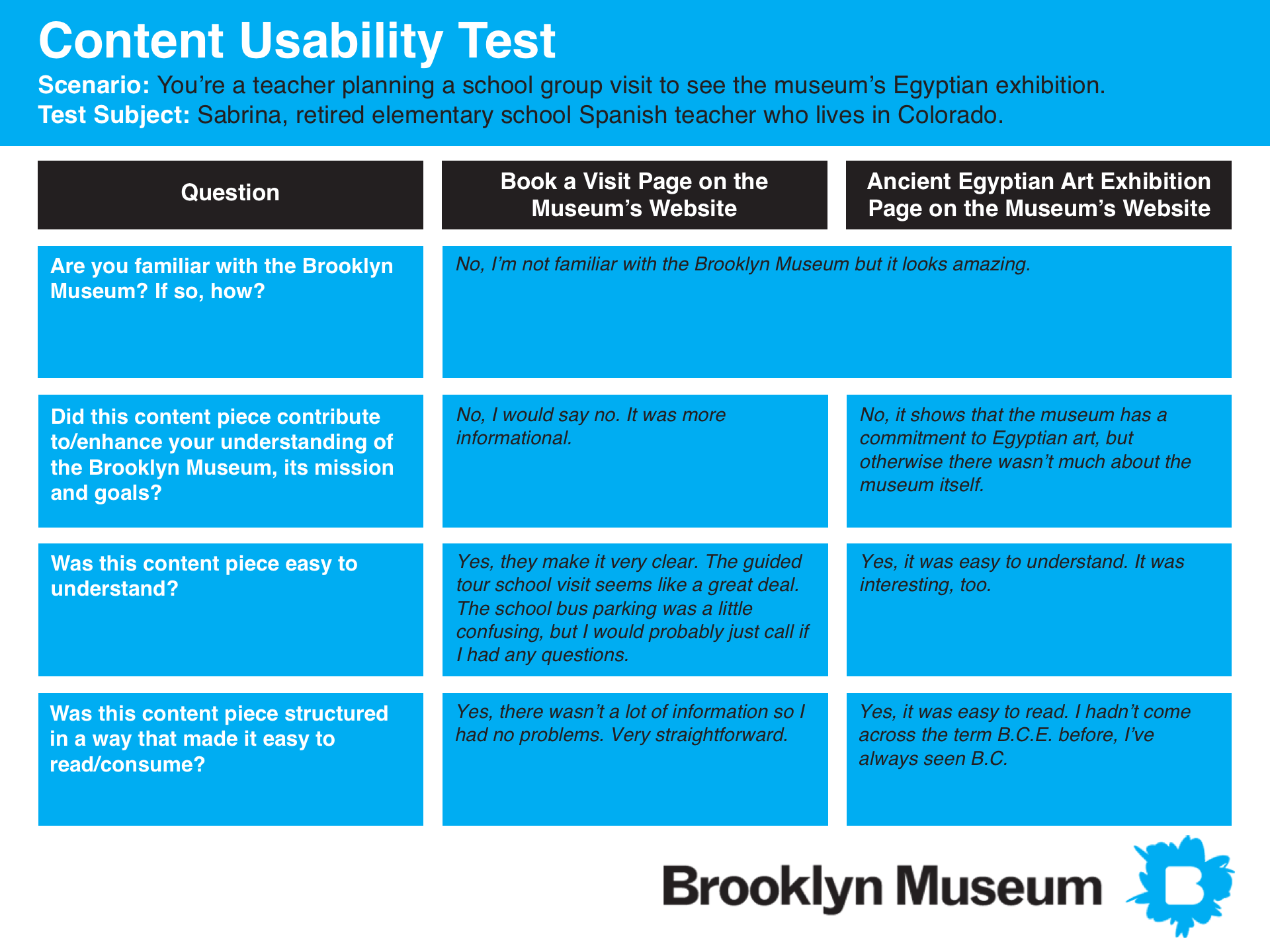

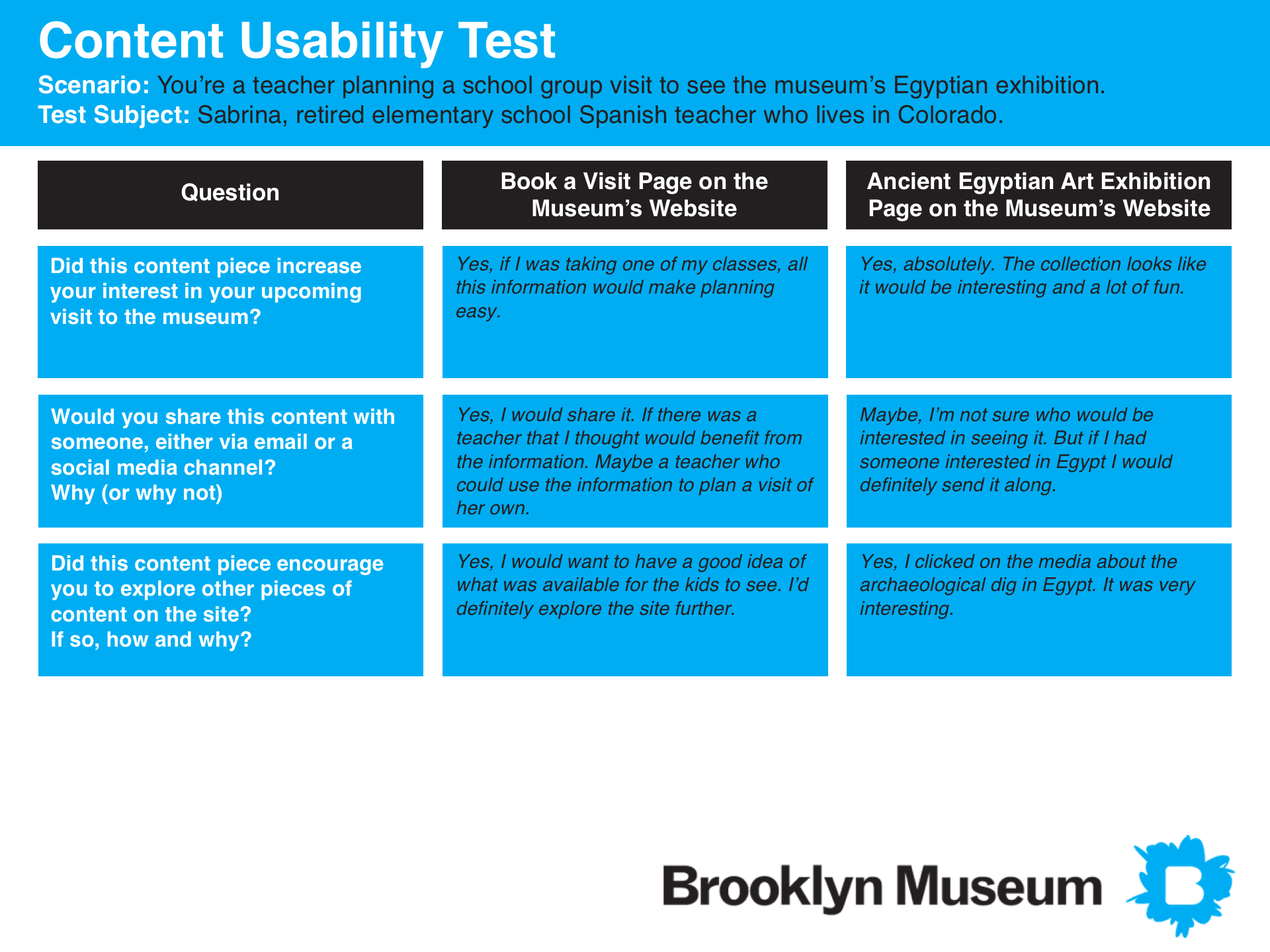

WEBSITE CONTENT USER TESTS

To supplement the quantitative data we collected during the website content audit our team administered brief content user tests. These content user tests helped us to better understand how well suited the website's content was to its users. Each test would focus on one of the six target personas; we chose which based on the user populations most likely to visit the sections we explored during our website content audit. Having looked at the Education and Exhibitions sections, I selected the Arts Educator persona to be the focus of my content user test. I then found two educators whom regularly teach art to their students, provided them with a scenario, and asked them to explore two webpages I selected pertinent to the scenario. (My questions and the participants' answers have been included in the figure below). Although the scope of these tests were very narrow, I learned that the museum's content is being written and presented in a manner that suits its users.

SOCIAL MEDIA CONTENT AUDIT

After completing our website content audit and subsequent content user tests, our team began to look at what was being published to the museum’s social media channels. My focus was on the museum’s YouTube and Tumblr channels (the figure below includes my analysis of both). Each of us used the same metrics (i.e., audience engagement, currency, etc.) when analyzing our respective social media channels; this allowed us to make more effective cross-channel comparisons. I discovered that the content being published to the museum's social media channels wasn't particularly well integrated into the museum's website, which was unfortunate because much of the content was unique.

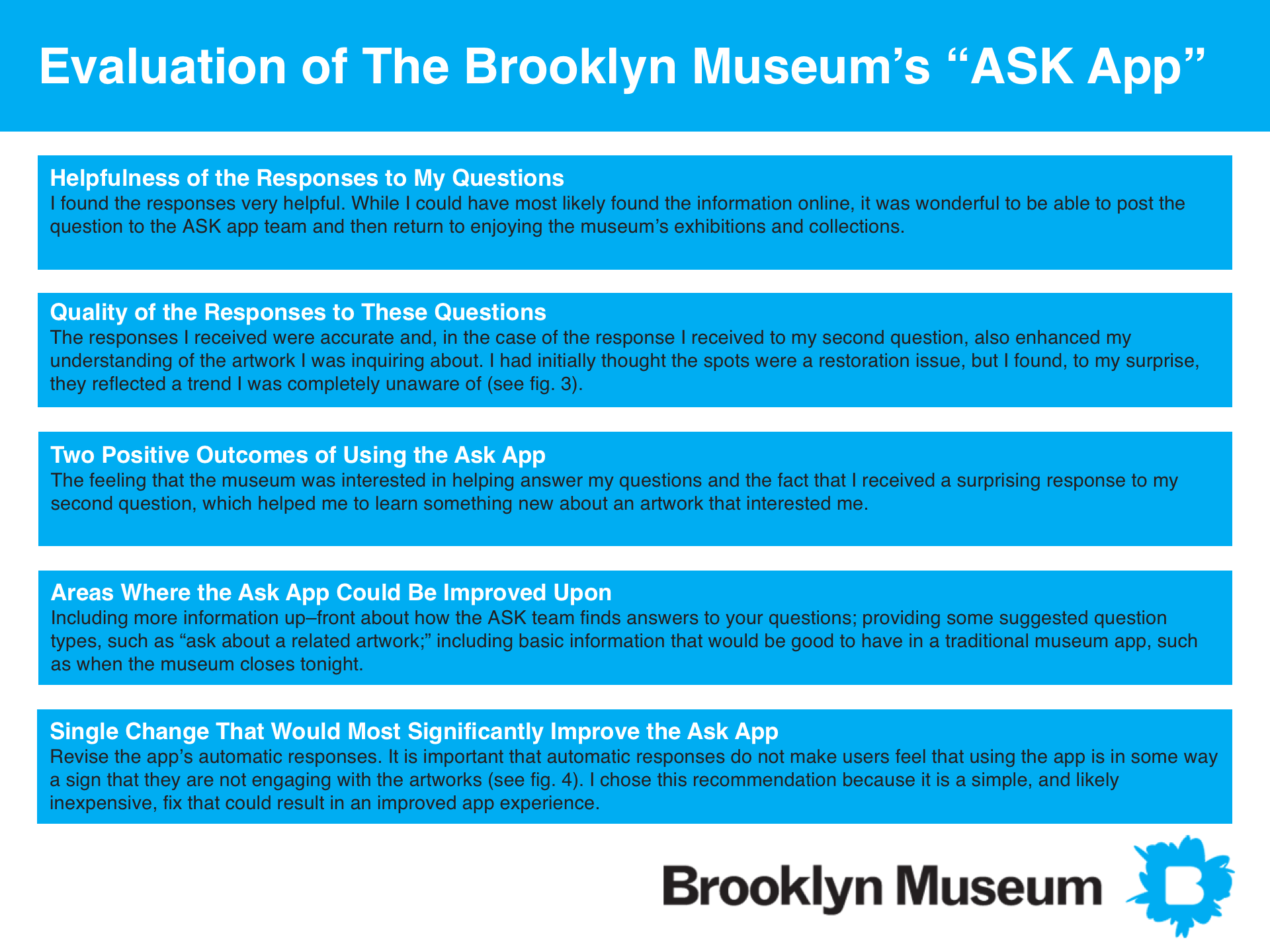

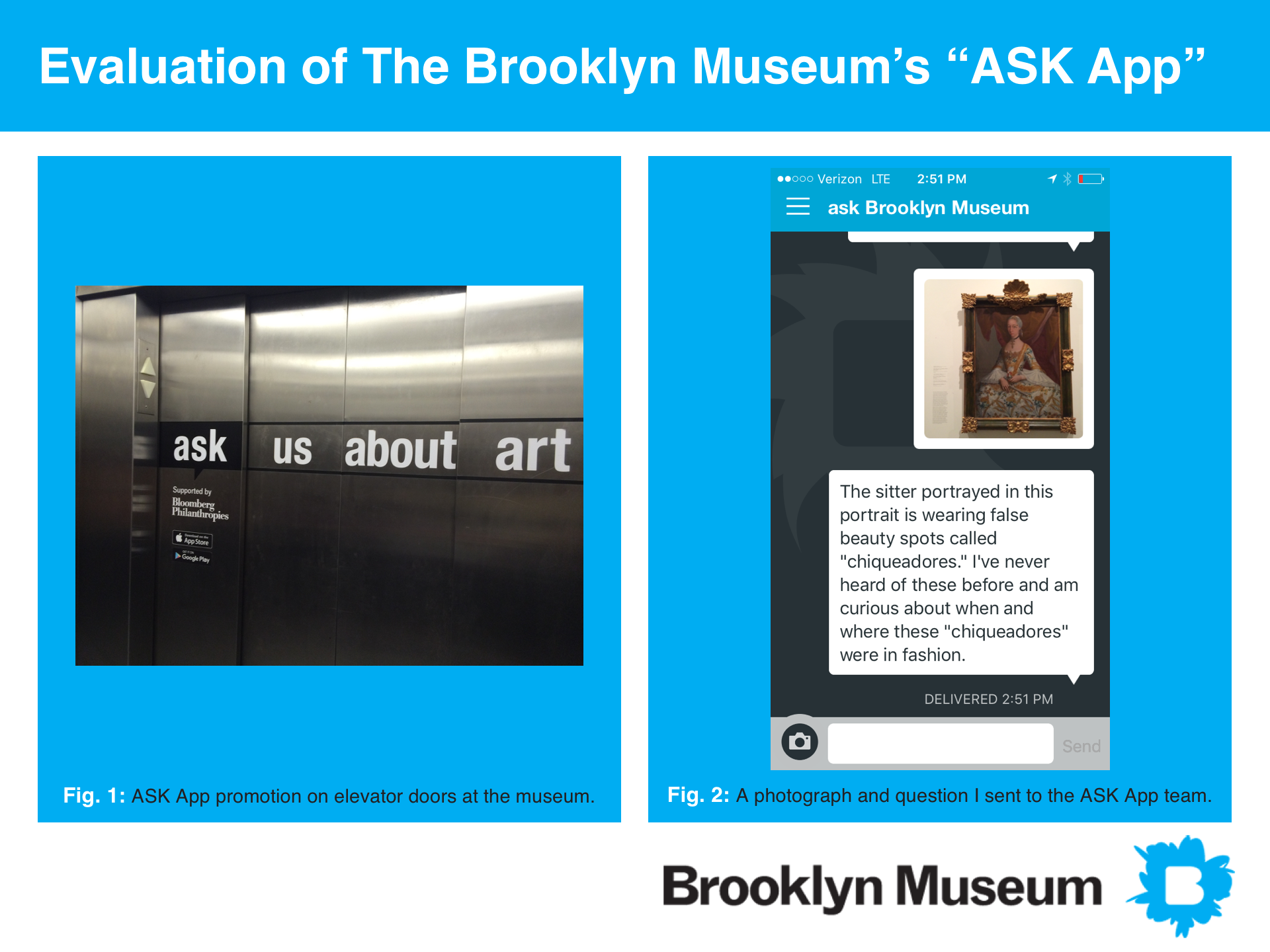

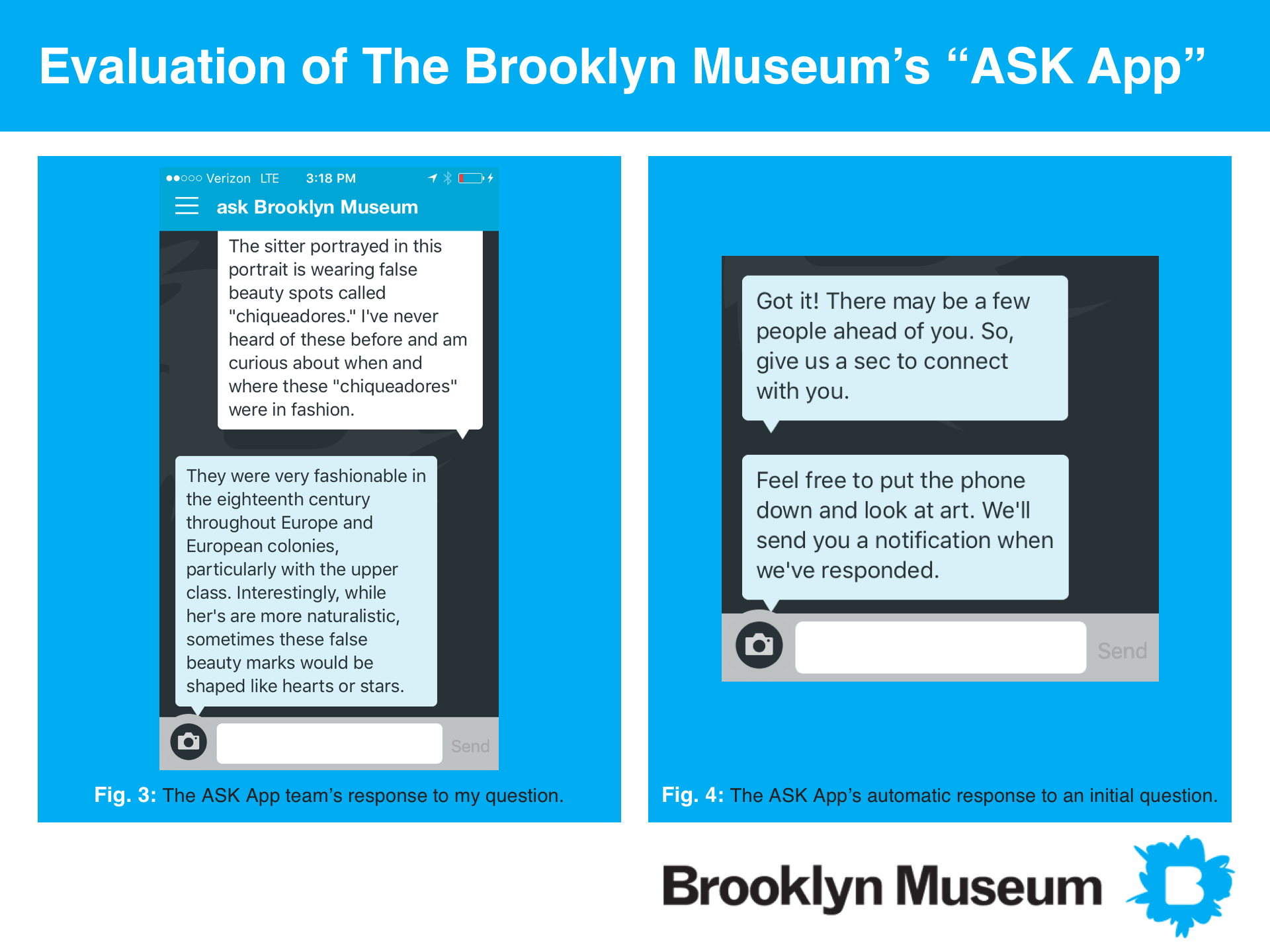

In order to complete the second step of our general content analysis, we needed to visit the museum itself. This site visit was necessary in order to experience the museum's ASK App, a native smartphone application that puts visitors in touch with the museum's team of art experts. These art experts can answer visitors' questions directly and provide further information about anything the visitor sees while they're at the museum. Upon arrival, each of us downloaded the app to our personal smartphone and used it as we explored the museum. (See the figure below for my analysis of the ASK App). I felt the app was an excellent tool for visitor engagement and was impressed by how well it was promoted within the museum.

While our content audits, user tests, and site visit helped us to better understand what content the museum was publishing and how it was being presented, one more step was needed before we could make an accurate assessment of how well the content was serving the museum's goals. Namely, we needed to investigate how similar institutions were publishing and presenting their own content. Each member of our team explored the website and social media channels of two museums with missions and/or collections similar to those of the Brooklyn Museum. I looked into the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), two California art museums with strong commitments to their respective communities. (An overview of my findings has been included in the figure below.) I found that both museums rely heavily on their social media channels to promote their programs and build engagement with their local communities.

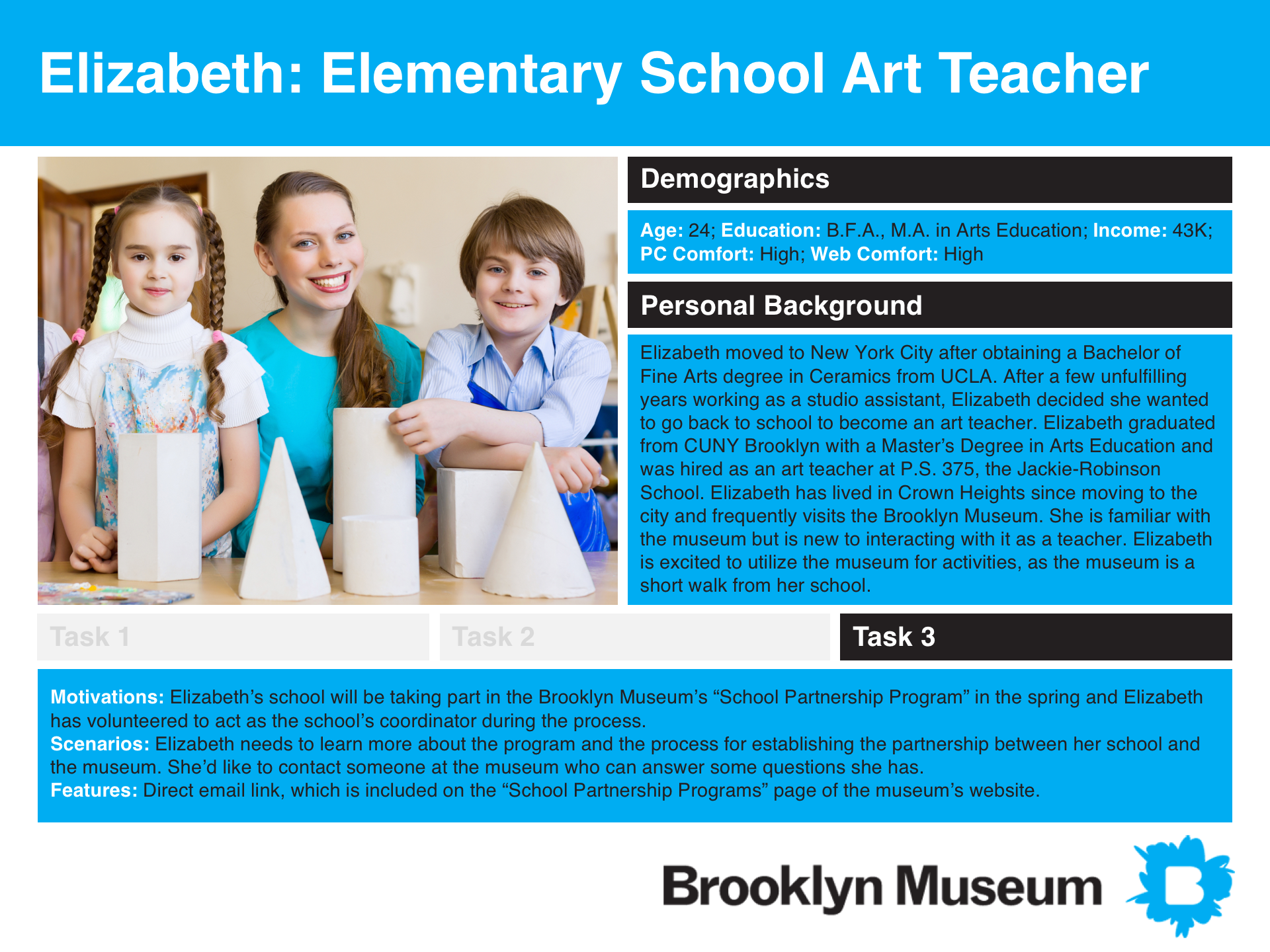

Having completed our general content analysis, our team felt we had a comprehensive overview of the museum's content and how it compared to similar institutions. We also felt we knew which of the museum's content was serving, or not serving, our six target personas (and by extension, the museum's goals). What we did not know, yet, was how effective this content might be in helping our six target personas complete tasks specific to their needs. Our first step in discovering if the museum's content was task-supporting was to outline three example tasks for each target persona. In order to better ground each of these personas in reality, we also provided them with an identity and a background. Each member of our team was responsible for the identity, background, and tasks for one persona. My work focused on the Arts Educator persona, whom I personified as Elizabeth, an elementary school art teacher. (Further details about Elizabeth and the three tasks I outlined for her (including motivations, scenarios, features, etc.) can be found in the figure below.) Outlining these tasks for Elizabeth helped me to realize that she would need quick access to clear, actionable content.

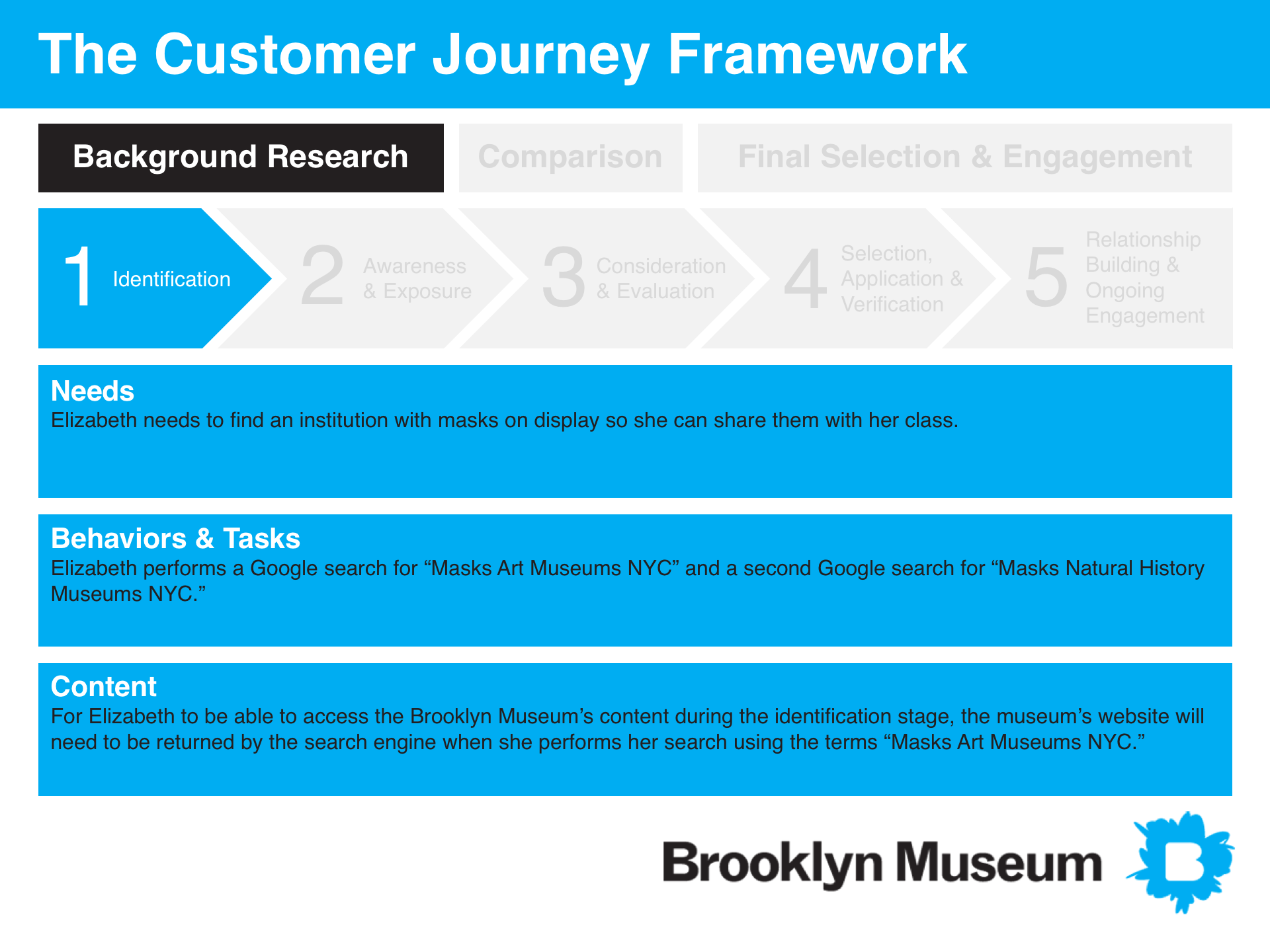

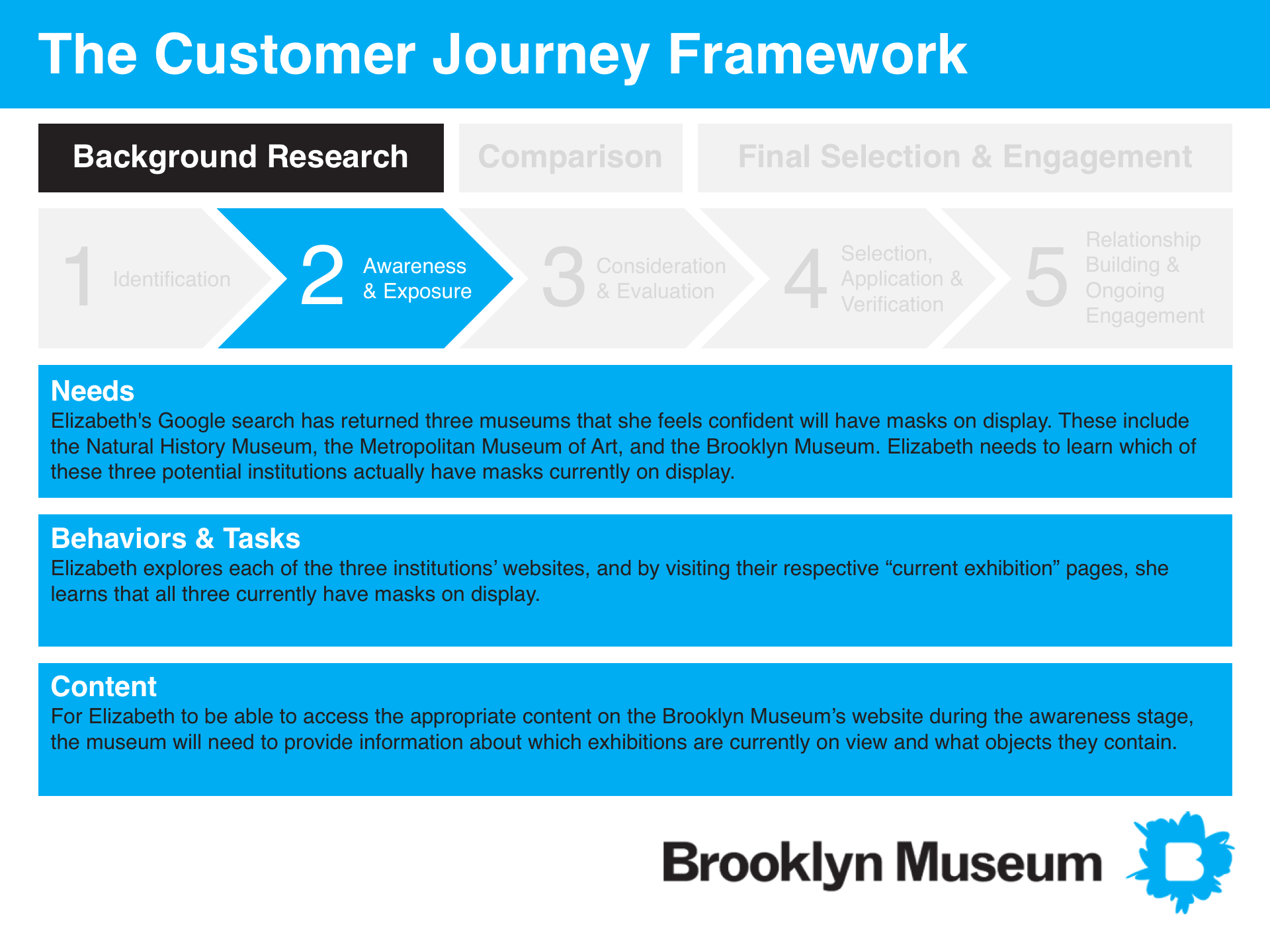

After creating our respective personas, we came together to discuss them. As a team, we looked for commonalities between our personas and the tasks we created for them. For each persona we selected one task, which we felt would be common to the largest population of actual users, to explore at a more granular level. We did this using the customer journey framework. (Details about this framework have been included in the figure below.)

APPLYING THE CUSTOMER JOURNEY FRAMEWORK

The task we selected for my persona, Elizabeth, focused on planning and facilitating a school trip to the museum. Using the customer journey framework to analyze Elizabeth's trajectory through the task was particularly helpful because it forced me to look at the task through a wider lens. I realized that the task didn't begin with the museum or its website; it began with a need (i.e., to find an institution with masks on display), which was not specific to any museum. This meant that in order for the museum to be able to fulfill Elizabeth's needs on their website, the museum's content must be discoverable from other websites (e.g., Google). (Elizabeth's complete journey, from identification through ongoing engagement, has been included in the figure below.)

With our general and task-supporting content analyses complete, our team knew what content was being made available by the museum and whether or not that content was supporting the needs of its target user populations. We next looked into how the museum was producing its content and explored ways in which the museum could improve its publishing efficiency by standardizing its production techniques. To do this each member of our team conducted an in-depth analysis of one piece of content published to serve the needs of our persona. The subject of my analysis was a teaching resource document, which helps educators talk to their students about the Francis Guy painting, Winter Scene in Brooklyn.

ANALYZING HOW THE DOCUMENT IS BEING PUBLISHED AND PRESENTED

I began my analysis by exploring how well the museum's chosen publication channel was serving the content and the needs of its users. I also looked into how the content was performing on desktop and mobile devices, noted which staff members were responsible for producing/reviewing it, and the amount of time they would need to do so. (My complete analysis has been included in the figure below.) I found that publishing this piece of content as a static PDF made interacting with it on mobile devices very difficult. In addition, the format makes editing/revising content after publication more difficult and time-consuming.

My publication and presentation analysis helped me to understand the inherent complexity of teaching resource documents and the importance of standardizing their means of production. With this in mind, I began work on content and metadata models that would help museum staff produce future teaching resource documents more efficiently.

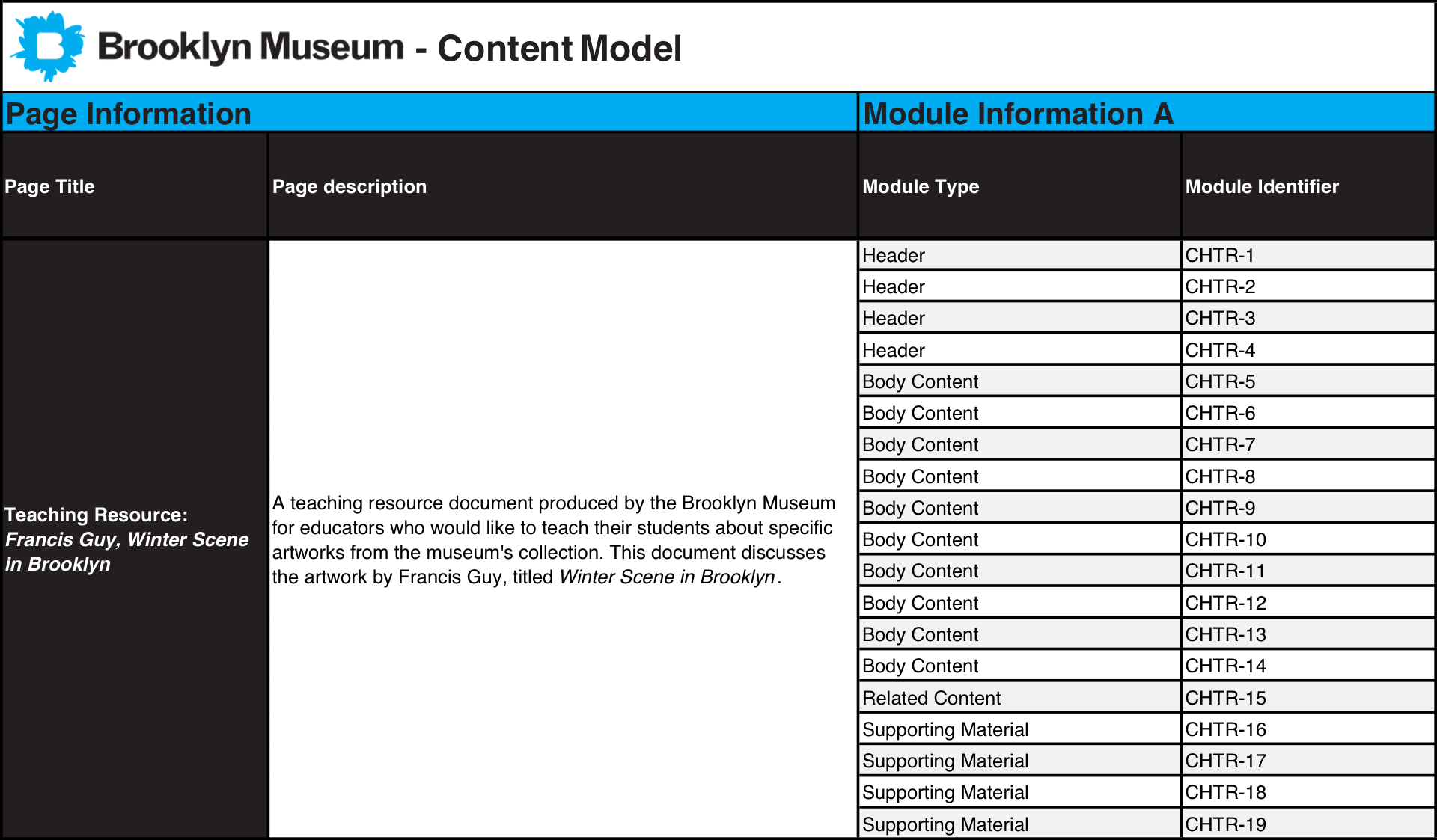

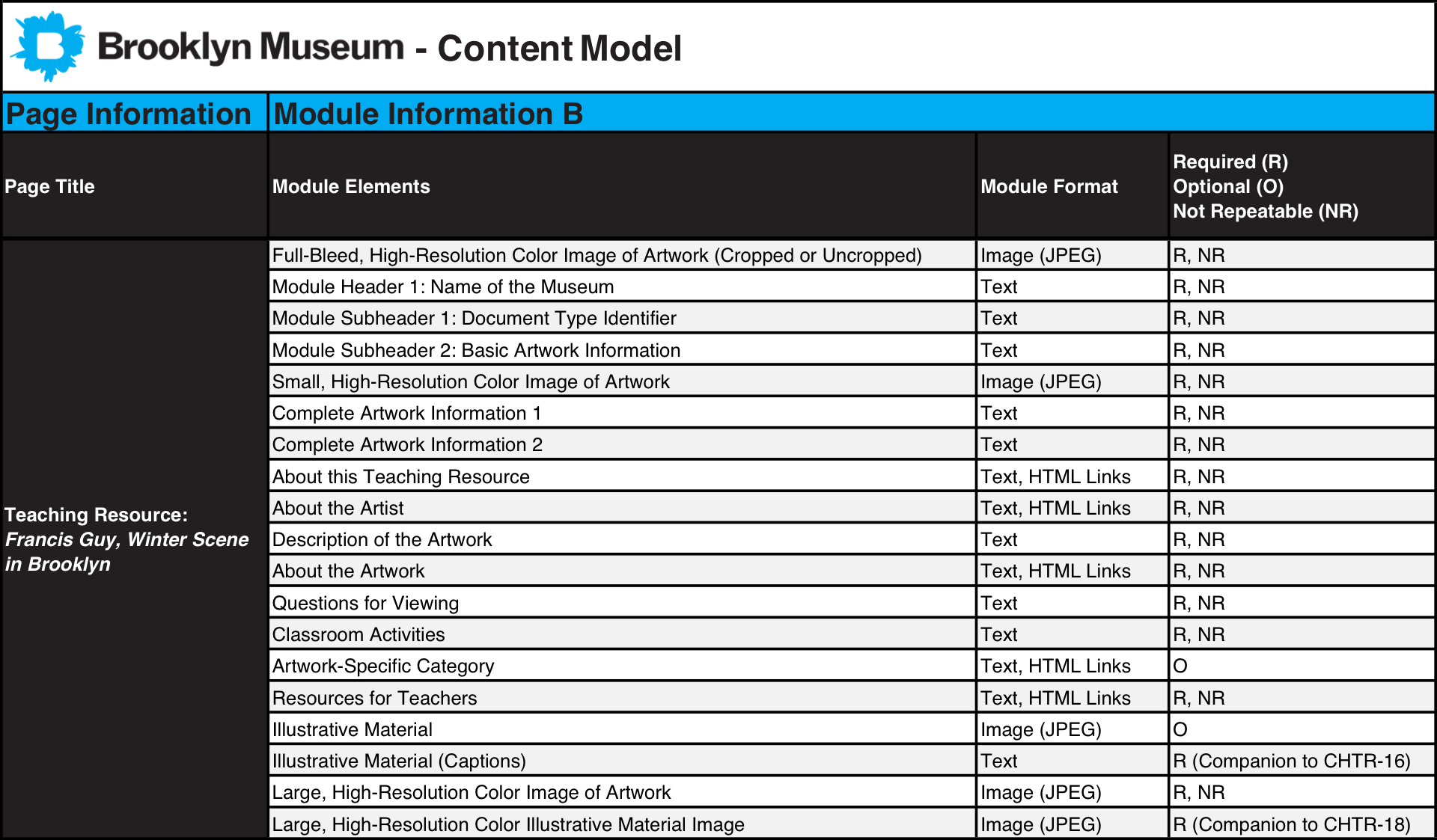

CONTENT MODEL

From the outset I knew that a detailed content model would do more than simply streamline teaching resource document production, it would also greatly benefit the educators who regularly use them. If the documents were given a standardized structure, educators who familiarized themselves with one could quickly and easily navigate others. I began by breaking up the document into individual modules, which I then assigned unique module identifiers. I next worked on classifying each module, determining the type of content it contained, it’s format, etc. I also provided content management system recommendations, which were later expanded upon as the content model was incorporated into the GatherContent platform. (The complete content model has been included in the figure below.)

METADATA MODEL

Following completion of the content model I began work on the metadata model. While both models have similar goals (i.e., standardization) their focus is slightly different; for content models, it's standardizing the information within a document, for metadata models, it's standardizing the information about the document itself. I included three types of metadata in my model: descriptive, administrative, and structural. I also included a folksonomy section with user-generated tags likely to be representative of those generated by actual users. The metadata model, as with the content model, was later incorporated into the GatherContent platform as well. (The complete metadata model has been included in the figure below.)

In order to make our content and metadata models more accessible to the museum’s staff, our team incorporated them into templates on the GatherContent (GC) content workflow platform. GC offers a suite of tools for producing, reviewing, and revising web content. GC can also be integrated into preexisting content management systems (CMS), so content produced using it could easily be uploaded to the museum's current CMS. For each module element in my template I included content guidelines and preferred formatting (where applicable). I also produced a document introduction with tone of voice guidelines and a module element diagram. (The document introduction, examples of my content/formatting guidelines, and the module element diagram have been included in the figures below.)

Our project culminated in a client presentation at the museum. In preparation, our team came together to look for common themes in the work we had been doing independently. We discovered the museum was already producing a good deal of content for all six of our target personas. What’s more, the content was largely being written and presented in a manner well suited to each (viz., the content employed appropriate terminology, tone of voice, etc.). The issue seemed to simply be that the content was not being exposed to the user populations it had been produced for. Our recommendation, given the museum’s financial limitations, was to standardize and optimize how their content was being produced (using our GC templates as a guide). This would be a low-cost, high-value way to help staff members spend less time producing content and more time working towards increasing its visibility.